Charles Manson, the end of Hollywood’s Golden Age & bloody cinematic fantasies

Analysing the Tate murders and two contemporary movies based on the crime

Recently Quentin Tarantino released the novelisation of his hit-film Once Upon A Time… In Hollywood (2019), and also announced that he is working on a stage play based on characters from the film, proving that the acclaimed director is far from done with his alternative history tale based on the Tate Murders. Neither was I, for Charles Manson and his following have intrigued me ever since I first heard about their gruesome crimes. They are grimly fascinating, not least because of their historical significance and sensational associations with cults, Hollywood and glamour, but because they represented the end of a cultural era. As Karina Longworth said in her podcast You Must Remember Manson, ‘The massacres Manson became responsible for wouldn’t just help kill off the sixties, and adding to a climate of paranoia that, for better or worse, inspired members of the Hollywood community who lived in fear that they could be next. Manson helped to invent the seventies, and that decades ground-breaking wave of new American films.’

Even now, after more than fifty years have passed, the story of the ex-convict turned cult leader and his following of drug-fueled hippies remain a subject of collective morbid fascination. In our true crime-obsessed post-Serial age, the murder case of actress Sharon Tate and her friends — having been adapted into countless books, movies, documentaries and tv-shows—is solidified as Hollywood’s most engaging true horror story. After watching Once Upon A Time… In Hollywood for the second time, I wanted to write a critical analysis on the movie as well as another, less prominent picture based on the Tate murders; The Haunting Of Sharon Tate (2019), which was released in the same year. Through analysing these two films, I want to shed a light on how modern cinema uses the Manson murders (in particular the Tate murders at Cielo Drive) as a vessel for bloody fantasies about the violent murders that supposedly helped to end Hollywood’s Golden Age. My goal is to dissect telling scenes from these two movies as to understand how contemporary (male) directors portrayed fantasies of masculinity and female victimhood in the films they based on the Manson’s horrors. For those that are not familiar with these murders, I start with brief exploration of Charles Manson’s most influental crimes and their place in pop culture.

The Tate/LaBianca murders

On the night of August 8–9, 1969, four members of the so-called Manson Family (a cultlike group of hippies led by Charles Manson, who resided at the Spahn movie ranch) invaded the rented home of actress Sharon Tate and movie director Roman Polanski at 10050 Cielo Drive, Los Angeles. They murdered Tate, who was eight months pregnant, along with their three friends — Voytek Frykowski, Jay Sebring, Abigail Folger. Steven Parent, an eightteen year old who was leaving the Polanski residence after visiting the caretaker, was also killed. The extremely violent murders were committed by Charles Denton ‘‘Tex’’ Watson, Susan Atkins, and Patricia Krenwinkel. Manson had ordered the murders because the previous owner of the house at which the deaths occurred — Terry Melcher, a music producer — had refused to make a record with him. The following night, Manson took the four murderers plus Leslie Van Houten and Clem Grogan for a drive, after which they stopped at a house at which they had once had a party, and proceeded to murder its owners; supermarket executive Leno LaBianca and his wife Rosemary, who was the co-owner of a dress shop. Much later, it would turn out that Manson, who was preparing his following for a apocalyptic race war he predicted, was also responsible for the failed murder attempt on Bernard Crowe (also known as ‘‘Lotsapoppa’’), the torture and death of music teacher/PHD-student Gary Allen Hinman and Hollywood stuntman/actor Donald Jerome Shea (also known as “Shorty”).

The Tate/LaBianca murders had a significant societal impact worldwide and are often described as a symbolic end for the ‘Swinging Sixties’, a period of love, peace and sexual freedom… that was seemingly already overdue. Writer Joan Didion described her recollection of the events beautifully in an essay in The White Album (1979): ‘Many people I know believe that the sixties ended abruptly on August 9, 1969, ended at the exact moment […] The tension broke that day. The paranoia was fulfilled.’

The brutal murders and the lengthy trials that ensued after Manson and the remains of his following were finally caught in Death Valley four months later, marked the end of the hippie era and gave way for a more conservative political time. ‘In the wake of the Tate-LaBianca slayings, Southern California was thrown into a panic and fear against the hippie movement.’ writes Donaghey for Vice, echoing the sentiment described by Didion. ‘The trust and idealism of the late 60s had curdled into paranoia, and the feeling carried well into the hangover of the early 1970s.’

Investigators found out that Manson had told members of his ‘family’ to kill those residing in Cielo Drive 10050, after a music producer — who used to live there — had declined to work with the aspiring musician. Although Manson didn’t kill anybody at the Polanksi/Tate residence with his own hands, the fact that he was involved in the planning and looked like the hippies that conservatives feared, quickly caused to media to turn him into a demon whose sinister motivations were eagerly attributed to his troubled upbringing and the decline of Christian morals in American society. During his prosecution, Manson revealed to be a highly disturbed, yet intelligent individual, immortalizing himself with quotes like this one: “These children that come at you with knives — they are your children. You taught them. I didn’t teach them. I just tried to help them stand up.” Aside from his memorable court appearances, Manson’s messiah-like behaviour and the female groupies that worshipped him only added further to his legendary status as the true perversion of the American Dream. ‘Manson achieved his goal, becoming so famous that his name replaced those of his victims. The crimes became known as the Manson murders.’ William McKeen wrote. Manson served a life sentence till his death in 2017.

Sharon Tate: token of victimhood

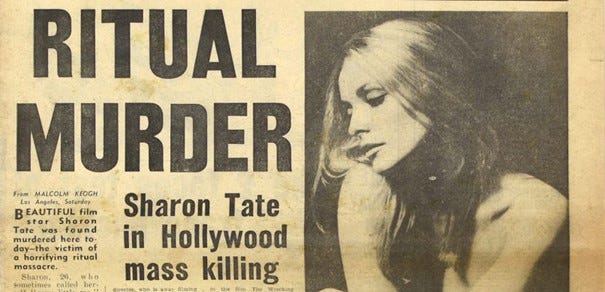

Despite the many victims of the Tate/Bianca murders, actress Sharon Tate remains the best-known and most glamorized of them all — the official casefile of the slaughter at Cielo Drive even starts with her last name. At the time of her death, she was 26 years old and eight months pregnant of a boy that was posthumously named Paul. Tate was also a beginning actress and model, who’d had small parts in a few major motion pictures like The Fearless Vampire Killers (1967). Before police finally zeroed in on Manson and his followers, Tate was the star of the headlines and glamorous pictures of her were featured on front pages. But it didn’t take long for Charles Manson to take her place. In the years following the crimes, he established himself as a cult figure. ‘If Manson didn’t live to memorialize his golden anniversary, the rest of us have, thanks to a Manson-industrial complex that has been working overtime. […] In addition to comic books and multiple websites devoted to him and his groupies, jewellery, coffee mugs, and T-shirts displaying his image sell on eBay, Etsy, and Amazon,’ Peter Biskind wrote for Esquire.

While the name Sharon Tate still rings a bell with many people, Charles Manson became an icon of evil. Kelly Wyne wrote about him for Newsweek; ‘Though America has had its history of cults and offensive behaviour, Manson’s influence of dozens of people, along with his behaviour until his death — he tattooed a swastika on his head in prison — was utterly captivating an unrelatable for so many, it continues to make news, movies and more, maybe just to show the darkness of humans, and how it can impact an entire community and country.’

The beautiful Sharon Tate, in contrast, remained another example of an aspiring starlet that died too young… her victimhood being, sadly, her biggest legacy. Her tragic story is as sensational as it is American, for she was a moderately successful star that found most of her fame in death. Her husband, Roman Polanski, went on to become one of the most succesful and celebrated film directors of his time, despite fleeing the United States after he was found guilty of the drugging and rape of a 13-year-old-girl in 1977.

Hollywood after Manson

The Tate/Bianca murders would go down in history as the symbolic end of the hippie era, and the societal shift marked the death of Hollywood’s Golden Age. As the Vietnam War was raging on and counterculture was demanding more space in the cultural and entertainment field, conventional genre movies and spaghetti Westerns that were so populair in the 50s and 60s made room for more experimental films characterized by their darker themes and explicit violence. Movies like Deliverance (1972), Black Christmas (1974) and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974) were deemed depraved and morally harmful by several critics at the time of their release in the early seventies, but they resonated with younger audiences, that seemed to be fed up with the predictable narratives of classical Hollywood movies. Perhaps their predictable structures and morally safe narratives didn’t suit the time where the Vietnam War divided the country and crime rates and drug use spiked all across the United States. It was also the time when serial killers like John Wayne Cagy, Ted Bundy and Richard ‘The Night Stalker’ Ramirez terrorized suburban America. Harold Schechter, a crime historian, even called the 1970s — 1999s the ‘Golden Age of serial murder,’ and found the reasons encompassing everything from sociological changes, to biology, technology and linguistics.

The Tate/Bianca murders, bridging two decades, formed the base of a new cinematic era. The first documentary film about Charles Manson released four years after the murders. Ever since, countless movies and series have been made about Manson and his crimes. Actor Damon Herriman even portrayed Charles Manson twice, first in the second season of Mindhunter (2017), and then in Quentin Tarantino’s Once Upon A Time… In Hollywood (2019). Hollywood’s fascination with the Manson family murders reached a peak in 2018, when no fewer than four projects based on the crimes were in production. The reason behind the many revisits of Tate’s murder were probably rooted in its fifty year anniversary, as well as an increased interest for everything (true) crime.

In many fictionalisations, Sharon Tate takes centre stage, arguably because she, as a victim, is the glue between the glamorous world of Hollywood and the dark underbelly of 1969 California that Manson represented. Despite still being a sensitive topic (some of the Manson family members, as well as Sharon Tate’s sisters are still alive and vocal), the tragic, sensational story of the beautiful actress getting murdered by tripping hippies is still frequently capitalized on by the entertainment industry. But aside from the sensational aspects, there must also a deeper, more disturbing reason behind Hollywood’s need to fictionalize the horrific crime over and over again. To further explore this, I will dissect two 2019 fiction films based on the Tate murders in the next part of this essay, as to further deconstruct how the sensational crime was and is used to convey fantasies of female victimhood and traditional masculinity. In the first analysis of Once Upon A Time… In Hollywood, I’ll reflect on the masculine fantasies that this film builds around the historical murder. In the analysis of The Haunting Of Sharon Tate, I’ll mainly focus on the film’s fantasies of female victimhood.

WARNING: Spoilers for Once Upon A Time… In Hollywood, The Haunting of Sharon Tate and Inglourious Basterds

Once Upon A Time… In Hollywood (2019)

Quentin Tarantino’s Once Upon A Time… In Hollywood was the only project that obtained the public backing of Debra Tate (Sharon’s sister). Despite this, the film — starring Hollywood veterans Brad Pitt, Leonardo DiCaprio and Margot Robbie — was the subject of multiple controversies. The first was based around the way Tarantino treats women in his movies. Another one stemmed from his ‘casual rewriting of historical events’. The third controversy was about the depiction of Bruce Lee, who is portrayed as an annoying caricature in a scene in the film. ‘At the core of all three of these ideas is that Hollywood is still a place that largely tells stories dominated from a cisgender, heterosexual white guy point of view,’ Emily vanderWerff claimed in an article for Vox. These controversies, however, didn’t stop the film from becoming a box office hit when it released in the summer of 2019. Critics praised the film for its ambiguity and strong performances, and it went on to win two Oscars at the Academy Awards.

Quentin Tarantino’s Once Upon A Time… In Hollywood has all the familiar tropes that the director is known for: bloody violence; dark humour; extensive dialogue and meta movie references. Still, this film feels more evocative and subtle than his earlier work. Perhaps this has to do with the fact that it might be his most personal project. ‘Tarantino was a boy of 6 in 1969, living far from the centre of Los Angeles, and in a sense what he’s done here is re-create the world he’s imagined the adults were living in at the time.’ Kenneth Turan wrote for the LA Times. The film focusses on the buddy-like relationship between the two male protagonists: a failing actor Rick Dalton (Leonardo DiCaprio) and his loyal stuntmen Cliff Booth (Brad Pitt) while Charles Manson and his Family members lurk in the background. ‘The relationship between Rick and Cliff is at the emotional heart of Once Upon A Time… In Hollywood, which openly pines for the carefree irresponsibility of youth.’ According to Katie Rife. The friendship between the two leads references the buddy-trope that drove many popular spaghetti westerns from the sixties, like The Big Gundown (1967) and Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969). ‘The pair function here a bit like Raymond Chandler’s tarnished knights, doing good despite themselves, an association heightened by a bookstore scene reminiscent of one in Humphrey Bogart’s “The Big Sleep.” Kenneth Turan wrote in his review.

Halfway through the film, aging stuntman Cliff Booth visits the infamous Spahn Ranch, in search for an associate producer. After Cliff finds out that the producer has become an apathetic victim of the Manson crew, he decides he can’t do anything for him. After Cliff Booth leaves the grounds, Pussycat (Margaret Qualley), an underage female hippie he has encountered before, confronts him (see figure 4). The camera pans up from her legs to her waist. We see her body in parts; the camera cuts off her legs and bottom; objectifying her. Cliff Booth walks past her indifferently, casually dismissing her. Just as the ‘tarnished knights’ starring in film noir didn’t allow themselves sexual diversions, Cliff doesn’t fall for the alluring trap that is this underage girl.

But then, he discovers that one of the hippies has stuck a knife in the tire of his ride. Visibly annoyed, Cliff stands in front of his bosses Cadillac, looking at the culprit (figure 5). Brad Pitt resembles legendary actor Robert Redford in his glory days; a heavily tanned, blond cowboy, looking like a Marlboro Man from a sixties advertisement. The hippie provocatively grins while Pitt’s character sighs at the childish act and dramatically takes off his glasses. The viewer can feel the tension rising, perhaps there is even reason enough to feel a little scared, for confrontation is now inevitable. But Cliff Booth, behaving like a stoic outlaw from a Sergio Leone film, stands firmly in his booths and asks the hippie rationally to replace the tire. Naturally, the fool declines. Then, Cliff Booth walks up to him and promptly punches him in the face, knocking him to the ground. The viewer can only cheer him on. Our flawed hero didn’t resort to violence right away; the antagonist was given a fair chance to solve the problem he caused. Therefore the beating feels justified— for in Tarantino’s world, one does not fuck with another man’s car; an overused symbol of manhood and American freedom.

Halfway into the film, we see main protagonist Rick Dalton’s neighbour Sharon Tate (Margot Robbie) strolling through downtown Los Angeles. The camera follows her legs as she casually heads towards the theatre on a sunlit Hollywood boulevard. Again; the camera is used as a tool of decapitation and disembodiment. The machinery of Hollywood cuts up Margot Robbie body into pieces; her legs become the subject of male desire. The viewer then watches Sharon Tate as she casually watches her own film, her feet resting on the chair in front of her. She is magnificently played by Robbie as a cheery but naïve blonde-embodying the male fantasy of a movie starlet. As someone who knows what happened to Tate in reality, these scenes feel slightly eerie… as a silence before the storm, as well as a way of setting up Sharon Tate as a somewhat childlike but sexual character, bursting with innocence and joy; representing a classical male fantasy of the passive and harmless beauty.

On a first watch, one can only look at these scenes with a sense of growing dread. But in the final scene Tarantino subverts the expectations of the viewer. Like he did in Inglorious Basterds (2009), where Adolf Hitler was brutally shot to pieces in the explosive climax, he now warps history into his own fantastic reality. ‘This is Tarantino’s most personal film in decades, and the longings expressed in it seem to flow directly from who he is as a person: an established middle-aged white guy confronting his own impending irrelevance,’ Katie Rife wrote for AVClub. ‘That exact prospect eats away at the film’s protagonist, Rick Dalton […], a fading Western TV star whose diminishing celebrity has forced him to contemplate the unthinkable for an actor of his calibre: going to Rome to star in “Eye-talian” Westerns.’

In the final scene, the Manson hippies enter Rick Dalton’s home, where they encounter Cliff Booth in the living room, who just lit a LSD-tipped cigarette. Charles ‘‘Tex’’ Watson says something about the devil and his deeds after which the intoxicated stuntman mocks him in response. One of the intruders asks Tex to shoot Cliff, but before he can, the stuntman whistles and his loyal pit-bull sinks his teeth into the flesh of the intruder. A violent battle engulfs, in which Cliff and his dog inflict brutal violence on the home invaders, which surpasses what a court would consider reasonable self-defence (figure 7). It is a show of violence and carnage for an audience that has been waiting for it for more than two hours. After the gunman is killed, one of the female intruders is mauled by the dog while another attacks Cliff with a knife. He overpowers her and slams her head repeatedly at several surfaces across the house (figure 8), including a framed movie poster with Rick Dalton’s face on it.

Rick Dalton is chilling in his pool with headphones on, not aware of the violence happening inside, when the last intruder (that’s still alive) runs towards the pool, screaming in agony. The fictionalised violence that made Rick famous finds its way into the film’s ‘reality’ in the form of an actual flamethrower, a prop that Rick has kept as a souvenir in his shed. He burns the screaming hippie to a crisp (figure 9), just as he did with the nazi’s in his most popular film, signifying that Manson’s hippies were a threat of similar severity; deserving the worst death imaginable — a cinematic death. When a neighbour from the Tate residence later comes to check if everyone’s all right, Dalton replies; ‘Well the fucking hippies aren’t, that’s for sure.’ Despite their swift reaction to the intruders, the protagonists are completely oblivious to the Manson threat over the course of the film. Nonetheless, Rick and Dalton end up as heroes, for with their action they save the only ‘pure’ and innocent woman in the film. All the other women in the film are portrayed as dangerous and untrustworthy… Pussycat is an alluring siren, Cliff Booth’s wife a nagging bitch and Lena Dunham’s character, who appears to be based on the Manson follower Catherine “Gypsy”, is a dangerous crook. In Tarantino’s universe, the extreme violence inflicted by the old school Hollywood archetypes saves society from the harsh reality in which a pregnant, innocent woman and her friends were tortured to death. The climax of bloodshed in Once Upon A Time… In Hollywood creates a moment of catharsis for the leading men; through killing the hippies, the aging has-beens finally have found meaning again. The brutal killings are justified, for the viewer knows that if the Manson hippies would have succeeded, all the characters would’ve been killed. The scene also seems symbolic for the relation between actor and stuntman; Cliff — loyal and unbothered by fame — does all the hard labour and ends up in the hospital, while Rick Dalton, — self-obsessed and vain — still manages to steal the show by getting the most glorious kill. Perhaps a comment on the actor’s fantasy of everlasting success and fame without really working for it. Maybe the brutal act is also meta-foreshadowing for the cinematic era that would follow soon; in which lighthearted genre movies would be replaced by films characterised by their brutal violence and depressing endings.

The film is a captivating, wistful fairy tale for aging men, a celebration of 1960s filmmaking in which the flawed but likable buddies save themselves and the innocent woman through the act of violence. Once Upon A Time… in Hollywood is Tarantino’s poignant love letter to classic Hollywood, as well as a emotional exploration into the masculine fantasies we construct for ourselves. The graphic violence that is commited against the intruders in the finale, is subtly justified by framing strong-willed and independent women as violent and dangerous. The corollary is masculine supremacy; the men in question are actually impotent and more or less useless, but through protecting their own fantasy, they are eventually redeemed. This narrative works on a meta-level as well: Quentin Tarantino, an aging Hollywood legend himself, has the power to change history inside the borders of his cinematic fantasy… to save Tate from her horrible death. Maybe Once Upon A Time… In Hollywood is the only movie so far that tackles one of Los Angeles’ most haunting crimes in a way that doesn’t feel exploitative or depraved, despite having one of the most violent endings ever seen in cinema. It is somewhat ironic, though, that a female actress that was constantly sexualised and objectified through her life, is posthumously celebrated by a male director known for warping history to indulge his own bloody fantasies. Despite the fact that Once Upon A Time… In Hollywood can be perceived as a glorification of male supremacy, Tarantino is gentle on the most sensitive aspect of the film and allows the viewer to leave the theatre with a sense of relief and optimism. Just like would always happen in the movies that died in the sixties, everything works out in the end.

When I mailed Charles D. ‘Tex’ Watson, who is now 75 years old and has long ago subverted to Christianity while serving a lifetime sentence in the California department of Corrections and Rehabilitation for his participation in the Manson murders, as to ask what he thought of Once Upon A Time… In Hollywood, he wrote that ‘the title is pretty much what I thought about it’ (figure 10). On my question of what he thought of the societal effects on our collective fascination for the cinematic re-enactment of historical crimes he answered ‘there is a computer acronym ‘‘gigo’’: garbage in, garbage out, or ‘‘we are what we eat.’’

The Haunting of Sharon Tate (2019)

Just as Once Upon A Time… In Hollywood, The Haunting of Sharon Tate is based on the 1969 Tate murders but with fictional elements. It follows actress Sharon Tate (Hilary Duff) who suffers premonitions of her murder at the hands of Charles Manson’s followers. The Haunting of Sharon Tate was written and produced before the plot of Once Upon A Time… In Hollywood was known, which suggests that both filmmakers came up with the concept for a feature film that warped the historical murders of Sharon Tate at roughly the same time. According to Kylie Harrington from The Hollywood Reporter, ‘He [director Daniel Farrands] combined the facts of Sharon Tate’s death with an alleged quote from her, published posthumously in Fate Magazine, where she recounted a nightmare eerily similar to her actual death. The result is a fictionalized version of the actress’ last 72 hours, incorporating elements of psycho-horror, slasher and home invasion movies.’ While Once Upon A Time… In Hollywood was a major Hollywood production with a 90 million dollar budget, The Haunting of Sharon Tate was allegedly made on a meagre budget less than 1 million dollars and was shot in just two weeks. Prior to the release of the film, Sharon Tate’s sister Debra publicly rebuked the project in an interview given to People Magazine. Among the many reasons for lambasting the film, Debra claimed the film was “classless” and “exploitative.” The Haunting of Sharon Tate was slammed by critics and was nominated for the Golden Raspberry Awards for worst picture. Hillary Duff won ‘worst actress’ for her portrayal as Sharon Tate. The film was a major box office flop; grossing only $68,504 after DVD and Blu-Ray sales.

The film starts with a black-and-white montage of an interview with Sharon Tate, in which she recounts a nightmare; suggesting she foresaw the terrible murders. The Haunting of Sharon Tate then switches to the morning after the slaughter, in which the camera slowly pans past the victims at Cielo Drive; ending with a brief shot of Sharon Tate’s mangled body inside the living room. What’s noticeable is the level of craft and accuracy with which the ‘bodies’ are replicated (figure 11 and 12). This early scene is eerie in its simplicity; an account of the silent dead lying butchered in a beautiful mansion overlooking Hollywood in the morning sun.

After this harrowing beginning, the movie flashes back in time to follow the very pregnant Sharon Tate, as she waits for her husband Roman Polanski to return from London, where he is finishing a movie. Her friends, Jay Sebring (Jonathan Bennett), Abigail Folger ((Lydia Hearst-Shaw) and Wojciech Frykowski (Pawel Szajda) keep her company in the meantime. In contrast to Quentin Tarantino’s 2019 film, which is centred on two male protagonists, The Haunting of Sharon Tate focusses mainly on Sharon Tate. Hillary Duff portrays her as a intuitive and caring woman who grows increasingly paranoid as her nightmares worsen and her friends interfere with the management of her home. At some point, her friends even start to worry about Sharon Tate’s mental health, attributing her anxiety and nightmares to pregnancy-related tiredness and paranoia. This narrative trope (the sensitive protagonist that realise something’s amiss but is ignored, belittled or treated in a condescending way by the other characters, who try to rationalise the supernatural warning signs) is often used in haunted house horror movies and can be interpreted as criticism on the way society belittles intuitive and sensitive women. ‘There’s something unsavoury about presenting Sharon Tate as one of the crazy ones,’ Wes Greene wrote for Slant, but one could argue just as well that the opposite is true; Duff’s Tate seems to be the only one in the doomed residence that is intuitive and smart enough to foresee the horrors that loom over their heads (or have already happened, considering your take on the ending, which I will discuss later).

Halfway through the film, the Cielo Drive murders play out in a shocking and bloody sequence similar to that described in police reports and the court proceedings that followed after the capture of the Manson Family in october 1969. Everything plays out similarly to what truly happened according to forensic reports and testimonies: Steven Parent (Ryan Cargill) is shot in his car by Charles ‘Tex’ Watson (Tyler Johnson). Tex then enters the home with the other family members and shoots Jay Sebring (Jonathan Bennett) in the stomach after he protests the poor treatment of Sharon. He then stabs and finished Jay off as he crawls through the garden, while Abigail Folger makes her escape but is caught up and stabbed in the chest by Patricia Krenwinkel until she is dead. Tate is the last one to be killed; Susan Atkins (Bella Poppa) stabs her multiple times in the stomach and chest. The scene is disturbingly brutal and the first scene to brand the film as a schlocky slasher — almost nothing is left to the imagination. In the final scene, that also functions as an agonizing metaphor, Sharon Tate, tied up, is stabbed to death in front of a blanket with the American flag on it (see figure 13); an object that was really present in the room when Tate was killed and Charles Manson himself apparently moved around after he visited to home some time after the murders. After the slaying, Sharon wakes up screaming. The nightmare (or perhaps a memory?) feels like an easy excuse to visualise the most brutal violence subjected to the victims, as it really happened. This scene makes it clear that The Haunting of Sharon Tate is — above all else — a slasher with an exploitative nature. It is somewhat ironic that the slasher genre, which sprung from the dark and cynical cinematic trends that were established after the Tate/Bianca murder, has finally produced a slasher that is based on the murders that allowed for the genre’s rise itself. It’s hard to argue with the exploitative nature of these scenes, which clearly was put in to shock and disturb to viewer.

After roughly an hour of ominous foreshadowing, more nightmares and supernatural events (such as a tape player starting to play Manson’s music in the middle of the night), the film turns into a fairly straight up home invasion movie, similar to modern horror movies like The Strangers (2008) and The Purge (2013).

Now the roles are reversed, and Jay Sebring gets the first kill when he pushes Atkins who then fatally hits her head into a fireplace. Voytek Frykowski fights off the other assailant and proceeds to drown her in the bathtub (see figure 14). Just as in the climactic scene from Once Upon A Time… In Hollywood (in which Cliff Booth kills the assailants) the movie doesn’t shy away from showing the violence against women; finding a moment of catharsis in a male victim overpowering and eventually ending the life of one of the female assailants.

Steven Parent flees with Sharon and tries to call the police with a radio, but is unsuccessful. In a redemptive twist, Sharon Tate takes away the gun of Tex Watson and finishes him off after he is smacked in the neck by Steven Parent (see figure 15). Sharon Tate brings some form of catharsis to the viewer, by reversing the violence. By turning history on its head and ending the life of the male assailant (Tex Watson is the main antagonist in The Haunting Of Sharon Tate) the movie explores what would’ve happened if the victims would’ve fought back against their assailants. The climax paints Sharon Tate as a typical ‘final girl’; an archetype coined by Carol J. Clover in her book Men, Women and Chainsaws: Gender in the Modern Horror Film which refers to the last girl or woman alive to confront the killer, ostensibly the one left to tell the story. Considering the fact that The Haunting Of Sharon Tate is a slasher film, is it useful to consider this archetype. ‘Detached from her low-budget origins and messier meanings, she now circulates in these mostly cleaner and more upscale venues as a ‘female avenger’, triumphant feminist hero,’ and the like.’ The final girl trope is often considered to be a rather onedimensional fantasy of an attractive female character with the skills and capabilities of a young man. Director Daniel Farrands does little to steer away from the archetype. He clearly aimed to change Sharon Tate, a token of victimhood, into somewhat of an avenger, but then undoes this attempt in the final scene.

After the survivors gather at the front of the house, any notion of a happy ending is crushed when Sharon Tate discovers that there are bodies in front of the house. Sharon Tate watches in horror as she lifts the sheet that is covering her own body… revealing that she is a ghost… and her survival was a fantasy all along (see figure 16).

In an interview with Gruesome Magazine, director Daniel Farrands stated that: ‘None of the movie is supposed to be a retelling of the exact events. […] in the story they’re all ghosts… no one is alive when it starts. No one is alive when it ends. […] everything that plays out is their souls trapped in some sort of limbo, or purgatory and they’re having to work out the trauma of what just happened to them.’ Despite this fairly logical explanation, this layer went over the head of most reviewers. David Ehrlich described the movie as ‘a cheap revenge fantasy that suggests its subjects only died because they couldn’t see the writing on the wall.’ Maybe the film is indeed a revenge fantasy; but not one aimed at Manson and his following. As Karina Longworth put it the first episode of her podcast You Must Remember Manson: ‘It’s hard not to see [the Tate murders] as the fulfilled revenge fantasy of one of the millions of pilgrims that come to Hollywood, looking to make their mark, only to be condescended and lied to and turned to away with nothing to show for their efforts.’ Maybe the low-budget horror flick should be considered as a cynical reflection on the ignorance and vulnerability of the wealthy Hollywood elite and the looming darkness that they should’ve seen coming.

The Haunting Of Sharon Tate, however, doesn’t has the confidence to be coherently cynical. Parts of it can be perceived as an empowering fantasy, while other scenes tastelessly exploit the Tate murders for cheap thrills. the film is largely a messy collection of worn out tropes of different horror genres, but despite this, the film offers an interesting display female victimhood as perceived through the male gaze, which comes in many forms.